Alexander Skarsgård: The Empire Interview

ALEXANDER SKARSGÅRD has always been drawn towards anarchy: disruptive...

ALEXANDER SKARSGÅRD has always been drawn towards anarchy: disruptive characters who turn worlds upside down. Now, as he plays a rogue android in Murderbot, we meet him to discover what pushes his buttons

“Is there blood in my hair?”, asked Alexander Skarsgård’s Eric Northman, having just killed, dismembered and feasted upon some unlucky soul in HBO’s vampire saga True Blood. For many, the show (2008-2014, RIP) was their first exposure to Skarsgård, who was starting as he meant to go on: anarchic, provocative, and unafraid to play characters with an unhealthy moral compass.

True Blood wasn’t *quite* the start. The son of Stellan Skarsgård, he acted in a few things as a child in Sweden before jacking it in, then appeared in 2001’s Zoolander, playing a model, Meekus, who gets blown up in a petrol station. After spending a few years in the Hollywood wilderness, Skarsgård finally broke through as Brad ‘Iceman’ Colbert in HBO’s US Marine mini-series Generation Kill (2008); True Blood began airing mere weeks later, and he was off to the races, going on to play dubious gentlemen in the likes of David E. Kelley’s Big Little Lies (physically abusive husband Perry), Robert Eggers’ The Northman (Viking on a revenge-mission to Hell – or, at least, Valhalla), and Brandon Cronenberg’s Infinity Pool (holidaying author who accidentally kills someone, escaping jail by having a clone of himself get stabbed to death, precipitating a series of clones that each get mentally and brutally pummelled – worst holiday *ever*).

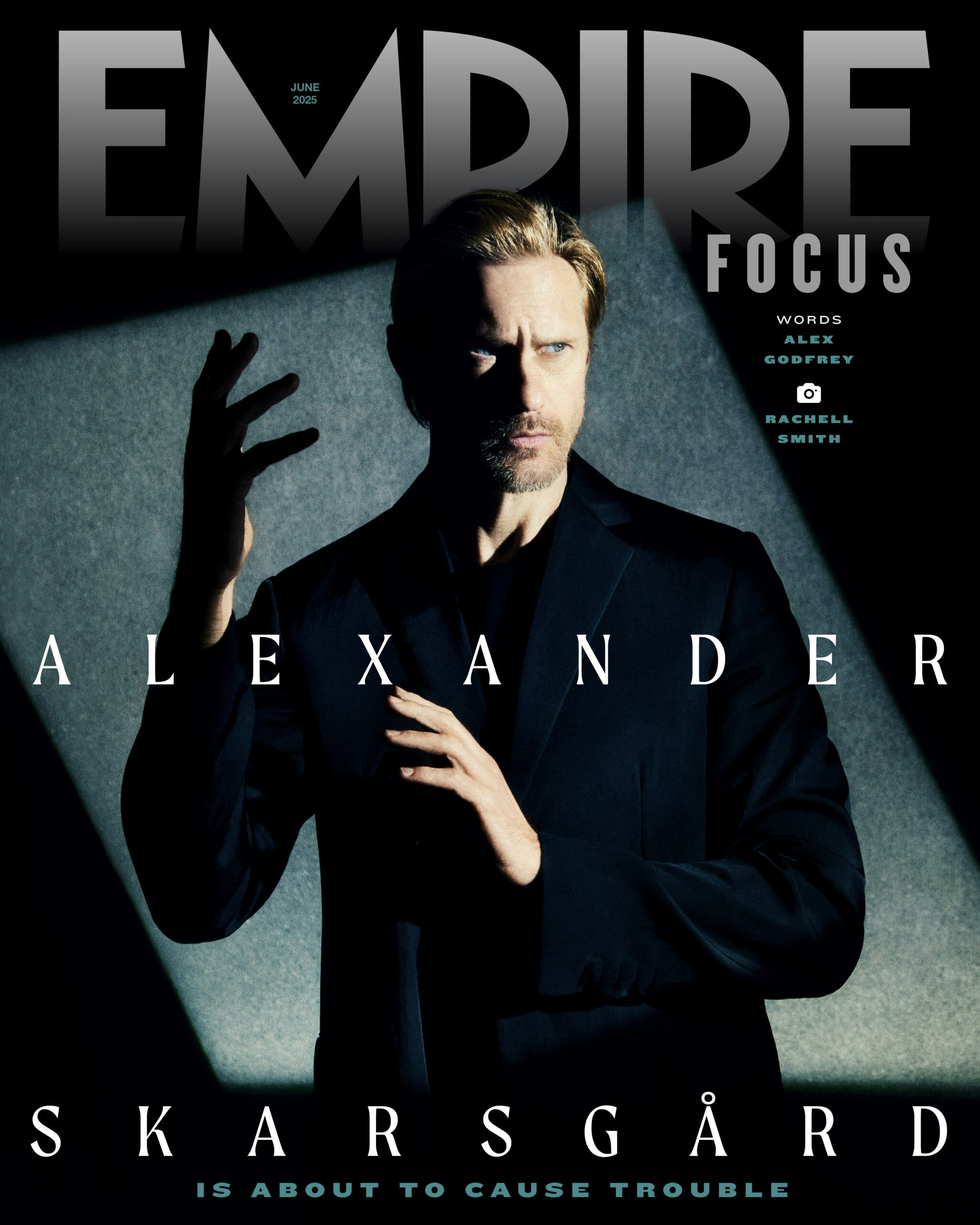

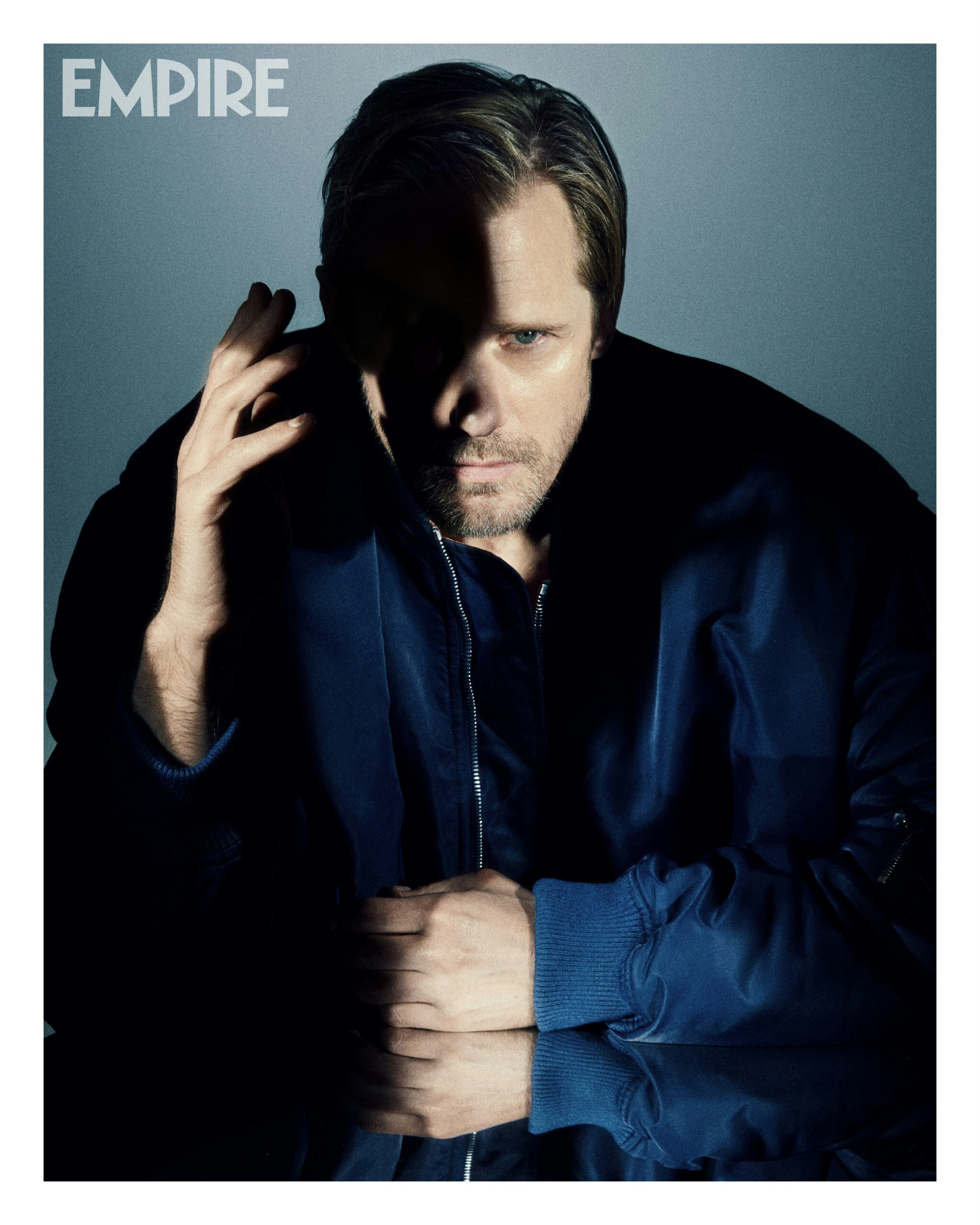

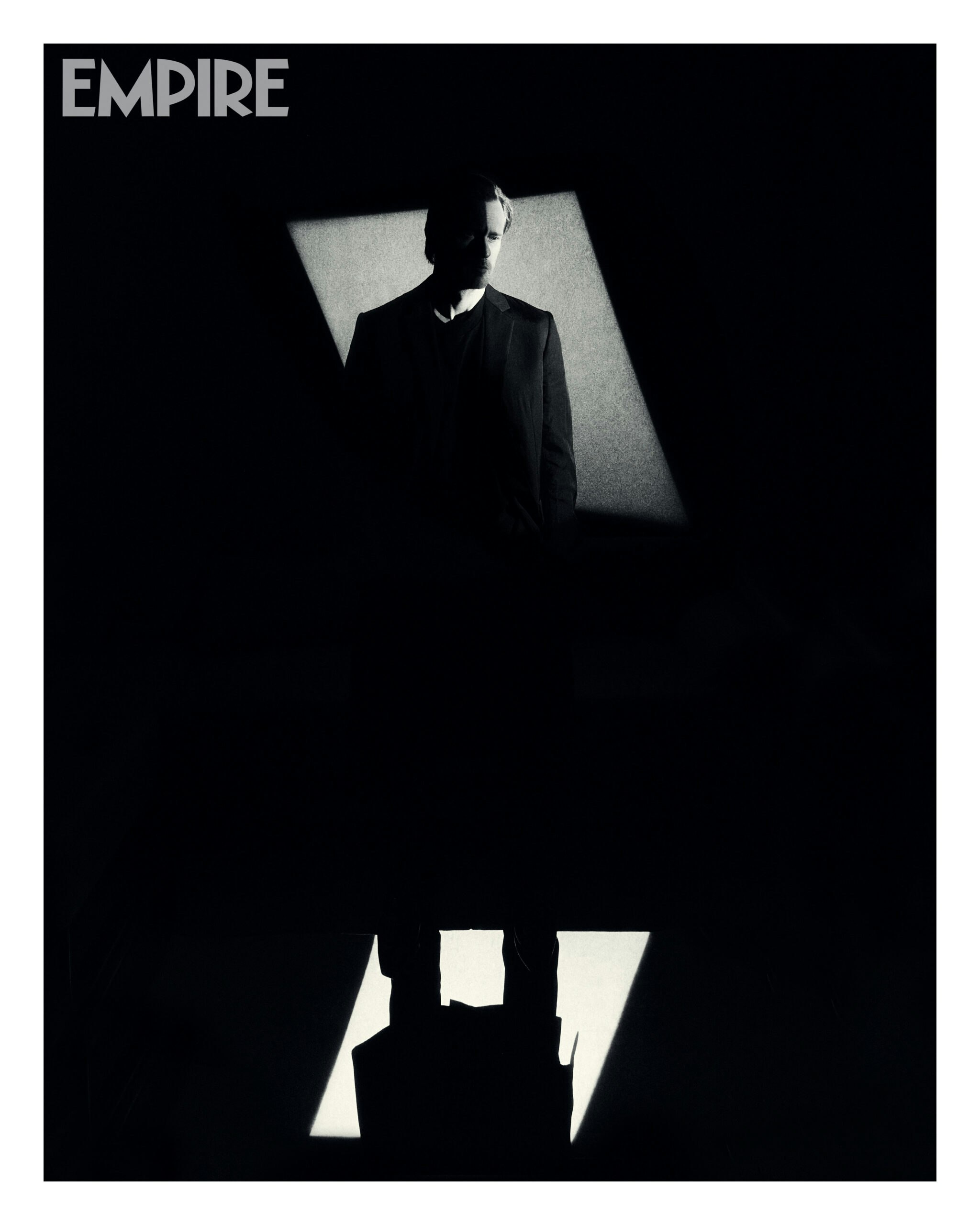

Now, Skarsgård takes the lead in Chris and Paul Weitz’s TV comedy-drama Murderbot, in which his privately snarky android finds itself free of corporate enslavement but can’t be bothered to do much about it. Photographing the actor last month in London, Empire then sat down with him to find out where all this mischief comes from…

A lot of your characters – certainly in True Blood****, The Diary Of A Teenage Girl****, Big Little Lies****, The Northman****, Succession – stir things up. They’re provocative. They push at things.

Yeah, some intentionally and some unintentionally. Some characters can be quite naive and childish and plain, but then either transform or are thrown into a situation that they can’t handle, and then it spirals into madness and they try to navigate that. It’s not something that I’ve set out to find in projects that I choose, but subconsciously, it’s probably true that I’m drawn to characters that, like you said, stir things up a bit.

Yes – even if they’re not aware of it, or if it’s not voluntary, they are disruptors. And I get the sense that that appeals to you.

Yeah, totally. And… why is that? (*Long pause*) Maybe because I was… steeped in the Swedish culture of conformity, and of following rules and politely waiting line. Maybe that triggered a kind of... a desire for anarchy.

Well, also – and this goes right back to Generation Kill – a lot of your work explores the idea of masculinity, of men’s obsession with what they’re supposed to be. When there’s too much testosterone going around.

Yeah, I mean, I didn’t choose Generation Kill. Generation Kill chose me (*Laughs*). I was not, at the time in my career, in a position to choose at all. I was incredibly lucky after years of not working to land that role. And again, it wasn’t because I have good taste. I was auditioning for everything. I did Zoolander in 2001 and we shot Generation Kill in 2007, and in those years in between I was primarily based in LA, doing odd jobs, auditioning. I played a supporting role in Hitch, with Will Smith, a romcom, and I was incredibly excited. I was playing Amber Valletta’s character’s douchebag ex-boyfriend. I was over the moon, because it was a big movie. I hadn’t worked in a couple years, and then I got that job, and I was like, “I’m in a fucking Will Smith movie, this is amazing,” and it was a fun character. I did a couple of weeks on that, and then my entire storyline got cut out of the movie, and all that’s left is a black and white photo in a newspaper where they refer to her ex-boyfriend. So I was pretty gutted. But I wasn’t surprised, because my character was a subplot of a subplot: I thought, “If they’re gonna cut something out of this movie, this character is probably gonna go.”

And other than that, I hadn’t really worked between Zoolander and Generation Kill. I was auditioning for a lot of terrible things. And so Generation Kill was just such an incredible opportunity. I was very fortunate that David Simon and Ed Burns, who had done The Wire, wanted a kind of a documentary take on it, so were intentionally going out to quite unknown actors, faces that weren’t recognisable. And yeah, there’s a lot of adrenaline and testosterone in that character [Brad Colbert] and in Generation Kill, but I liked that it wasn’t a cliché of a recon Marine.

He’s pretty soulful.

He’s very soulful, and he’s cerebral, and he is a patriot, but he can also see how fucked up everything is, and he carries a lot of frustration with his superiors and with the system and the bureaucracy. I’ve never really been interested in characters that are strong and tough. They can be strong and tough, but you want something underneath it. It’s got to be something conflicting, or an exploration of why they feel the need to present themselves as strong and tough. That’s what’s interesting.

I like the narrative that I was like, “Ego and vanity, not for me. I’m gonna step away from the spotlight.” But I think it had more to do with insecurity.

You do choose films that unpack that. In Infinity Pool****, James, a struggling author, gets all the masculinity – and ego – stripped away from him. A defining scene is when Mia Goth’s Gabi confesses to never having read his book after all and reads out a bad review to him. It’s possibly, in its own way, the most destructive thing that happens to him in that film, which is saying a lot. It really picks at ego. As an actor, I imagine that was something you enjoyed exploring.

Oh, yeah. It’s an elevated, twisted comedy but… I love the idea that he’s desperately holding on to the notion that he finally found a fan. He can’t believe his luck, at the beginning of the movie when she recognises him. She’s read his book. She loves the book. She recommends it to her husband, and he’s holding on to that throughout the film, throughout the madness of the movie. He’s like, “Well, at least she’s a fan.” Yeah, the sheer vanity of that really intrigued me.

You acted as a child but gave it up when you were 13, because you didn’t like the attention you were getting. It feels like there’s a throughline between what we’re talking about – stories that hold up vanity and ego to the microscope – and your outlook from an early age, of not being interested in that side of things.

Well... I’m quite vain and I have a huge ego. So that might be a bit too flattering of an interpretation of [what happened]. I like the narrative that I was like, “Ego and vanity, not for me. I’m gonna step away from the spotlight.” But I think it had more to do with insecurity. This TV film, Hunden Som Log – ‘The Smiling Dog’ – came out when I was 13, and suddenly I was not anonymous anymore. People would recognise me on the street, and I would get fan mail, and people would sometimes wait outside our apartment building in Stockholm for autographs. It’s a fucking weird age, for anyone, and... it threw me off a bit. It was scary to me. And any kind of attention I would get from girls, I would interpret as, “She’s only interested in me because she wants an autograph, or thinks it’s cool that I was in that movie.” And that gutted my self-confidence a bit, where I felt like, “I don’t have much worth. It’s just because they’ve seen me on television." And because I wasn’t dead set on becoming an actor, it wasn’t a difficult decision. I was like, “I don’t think I want to deal with this anymore.” And I didn’t for many years.

Indeed, at 19 you joined the Swedish Navy. Do you think what you experienced there inspired or informed some of the things you’ve been exploring as an actor? Obviously it was a very macho environment.

I was probably drawn to the military, into this specific unit, because it was... maybe a way for me to rebel against my artistic hippie family, where it was all very bohemian, lots of red wine and cigarettes and conversations about Albert Camus. Also, I was 19 and I had grown up in a very urban environment in Södermalm in central Stockholm. And on both sides of my family, my mom and dad’s side, they’re in the film industry, or they’re painters or writers, which was an incredible environment to grow up in, but I wanted to find myself, and my own path, and so I went against that. I got to pretend to be James Bond for a year and a half: our job was basically to secure the islands of the archipelago outside of Stockholm against sabotage or terrorist attempts on the island. There was no patriotic reason for me to join. I didn’t join to protect Sweden or because I liked guns. In terms of masculinity, some of our officers were physically very strong and imposing, but I was more impressed by the more thoughtful, more cerebral officers and fellow soldiers. I admired the ones that didn’t feel the need to show off or look cool. Because it was so obvious to me that the cool guys were the ones that *knew* they were cool. They didn’t have to show off, because that, to me, was a sign of insecurity. So I don’t know if that was the genesis of it, but to this day I feel that way: it’s such a sign of insecurity when you’re so aware of how others are going to perceive you. There’s a relaxed confidence in just knowing that you’re the shit. In Generation Kill, Brad Colbert wasn’t the physically strongest guy, but everyone knew that he was the best soldier, because he was fucking smart, and *that* made him really cool.

It’s interesting that you joined the military as a rebellion to an unconventional lifestyle, because in your work you’ve chosen films, and often directors, that are culturally disruptive.

Yeah. But I guess joining the military was also a disruption, because it was so unexpected for someone from my family to do that.

You’ve also often played characters that are conflicted and confused. In The Diary Of A Teenage Girl****, Big Little Lies****, The Northman****, Infinity Pool****… they’re not really in control of what they’re doing. And you find a way of playing them that really gets into the cracks.

That’s the most interesting challenge. For example, Perry in Big Little Lies: how do you avoid making him clichéd or cartoonish or too much of a Disney villain? When he’s remorseful, he’s genuinely remorseful. He is madly in love with his wife, and he’s a great dad to their twins. That gives the character complexity, and it was important to play those scenes with sincerity, to make it a real character, and someone who’s afraid of himself in a way, and what he’s capable of. Because without that it’d just be, “Oh, here’s the villain of the story.”

Is that why The Northman appealed to you too? Because that guy is a mess. Especially after his mum tells him that he’s got everything all wrong.

Absolutely, yeah. It’s a version of Hamlet, obviously, and what makes Hamlet great is the conflict of character, the friction within the character. And even if you’re making a big action movie like The Northman, I don’t see why you can’t have depth, and characters that make you lean in, and have you unsure of who you’re rooting for. And so yeah, that’s always more interesting.

Succession was fucking amazing.

When I spoke to you about The Northman in 2022 you said that, months on from filming it, you were finding it hard to connect with anything else you were being sent. You said, “I feel a bit lost, I don’t know where to go from here.” Do you remember that feeling? And how did you get over that?

Oh, I remember it vividly. And I don’t know how I got over it. If I ever did. (*Long pause*) No… it was such a monumental undertaking, and it had been eight years from its inception to when we talked. It was the hardest, most gruelling shoot of my life. So once we’d made it through, I felt like, “What the hell do I do now?” I don’t think I worked for a little while after that. Like I said in that interview, I was finding it hard to connect when I was sent scripts. I felt a bit... a little catatonic. I was just sitting at home and trying to focus, trying to read stuff and I was just like, “I don’t care. I don’t know. I don’t care.” I believe Succession was the next thing I did.

That’s a cool thing to bring you back.

Succession was fucking amazing. I’d seen the first two seasons, and I’d seen Peep Show before that, I was a big fan of Jesse Armstrong and Armando Iannucci, that whole gang, the British comedy royalty. When they reached out, it was supposed to be two episodes. There was no discussion of what would potentially happen in the future, it was just like, this crazy tech guy comes in and... stirs shit up (*Laughs*). So that helped me get back on the horse and find some excitement to be back on set, because it was only a few days’ work with people that I admire, on the greatest show on television.

And he’s another interesting character in terms of what we’ve been talking about, because he’s this ultra-successful tech bro but then he’s sending blood bricks to his ex-girlfriend. Crazy man shit.

Yeah. Well, when you’re surrounded by yaysayers and sycophants, sometimes you just want to fucking stir shit up and get a reaction. And I think he’s also curious to see how people will react if he does or says weird shit. He has an extremely short attention-span and finds most situations and most people quite dull.

As well as all of these idiosyncratic character studies, you’ve done a handful of huge films – Battleship****, The Legend Of Tarzan****, Godzilla Vs Kong****. Can you still do what you want to do, character-wise, within the confines of those big productions?

I’ve had really good creative relationships with all the directors that I’ve worked with on bigger movies, where they’ve been very open to creating a playful environment on set. So I’ve never felt stifled or creatively suffocated. But then the stakes are much higher, so you might have super fun coming up with cool side-stories or weird little aspects of the character, but then, when there’s hundreds of millions of dollars at stake, ultimately those eccentricities might not make the final cut.

Yes, it’s been speculated that your character in Godzilla Vs. Kong was something a little different, going through maybe a rough time, and that didn’t end up on screen. What’s it like when you’re on something like that and a character might change during production?

There was definitely more of a backstory, more character-driven scenes that ended up on the cutting-room floor. But if you sign up to do a movie like Godzilla Vs Kong, there are only two stars of that film. And you’re not one of them. Adam Wingard, the director, and I, can play around and come up with weird quirky shit, and add layers of character work. But at the end of the day, if they’re gonna cut down the film, Skarsgård will end up on the on the floor, not Godzilla or Kong (*Laughs*). So I totally get it, and, you know, the movie works. It didn’t need more Skarsgård.

In Murderbot****, you’re the lead, and are in more or less every scene for multiple episodes. That character has all this power, it can do whatever he wants but just doesn’t. For a while it’s just observing what the humans are doing.

Yeah. It can do whatever it wants, the universe is its oyster, but it has to come up with a plan, it can’t just take off – because then everyone will know it’s rogue, and then they will hunt it down and kill it. So it’s like, “Okay, I’m gonna bide my time and wait for the right opportunity.” It’s not interested in humans, humans are idiots. It’s kind of appalled by them, and it’s been treated horribly by all its clients up until this moment. But then it ends up on this weird planet with this weird group of humans that are outside the corporate system, and they don’t believe in indentured servitude, they want to talk to Murderbot and invite Murderbot in, instead of storing it in the tool shed, like other clients have done, and that freaks Murderbot out. So the story is about how it tries to not engage with the humans, or as little as possible. But they’re working so hard to connect with Murderbot that it’s starting to chip away at its armour, in a way where it’s slowly starting to care about them, which it finds disgusting.

How did you approach that evolution, of portraying a machine that is becoming a bit more human?

Ironically, I found Murderbot more relatable than most characters I’ve ever played.

Really?

Yeah, I found Murderbot incredibly relatable. There’s just a... There’s a social awkwardness, or just trying to figure out how to fit into a group.

Is that something you feel?

Well, it’s that feeling of walking into a room of strangers and you’re trying to read the situation in the room. I don’t have social anxiety, but I can definitely relate to the feeling where everything is slightly elevated when you’re surrounded by strangers, or you’re in a room with a lot of people, and you’re trying to figure out what’s going on. You’re desperately trying to leave the room, but you can’t, because you’re told to be here.

Is that what it feels like being an actor sometimes, at events?

Yeah (*Laughs*), sometimes I feel like an android in those moments, or I just want to pull the ripcord and get out of there. But also in the aspect of having life goals, but then procrastinating. Murderbot talks about having all these cool, fucking awesome adventures and badass stuff, but then… You might be dreaming about that, but then when you finally have a moment where it’s presented to you, it’s a big step to actually take the first step into that and start executing [it].

Let’s end on Infinity Pool****, because when we spoke about the film in 2023, you told me that you’d been given one of the clones, and that it was on its way to your house. Did it get there?

It got there. Yeah. It’s a version of my head in that red latex, the first time you see the clone, in that red goo.

Where did you put it?

I put it on my coffee table, but surprisingly, it freaked people the fuck out when they came over, so I couldn’t keep it there (*Laughs*). It didn’t quite work, because a bunch of my brothers have kids, four or five years old, and it didn’t quite fly when there was a very lifelike replica of my face coming out of red goo on the coffee table.

So where is it, in a cupboard?

Yes, it’s stored for now. I tried to figure out if I could hang it on a wall somewhere, but it freaks people out, surprisingly. Especially children. So, I’ll get back to you on it. Once I find the right spot for it. I mean, *I* love it. It’s my face, I love my face, what can I say?

Originally in the June 2025 issue of Empire. Giancarlo Esposito was shot exclusively for Empire in London on 12 March, 2025, by Rachell Smith. Murderbot is on Apple TV+ from 16 May.

What's Your Reaction?