Harris Dickinson On Directing Urchin, Pushing His Limits, And Preparing For Lennon

For the best part of a decade, Harris Dickinson has used the screen to portray...

For the best part of a decade, Harris Dickinson has used the screen to portray masculinity in all of its shades. From his startlingly vulnerable debut in 2017’s Beach Rats — which saw the London-born actor play a teen Brooklynite wrestling with his sexuality — Dickinson has never shied away from knotty men. Whether flying through the ring as a pro-wrestler in The Iron Claw or quietly scowling as a Larry David-esque Instagram boyfriend in Triangle Of Sadness, his characters have always been larger than the sum of their parts, yet grounded by Dickinson’s all-in approach, the result of humble beginnings and hard graft.

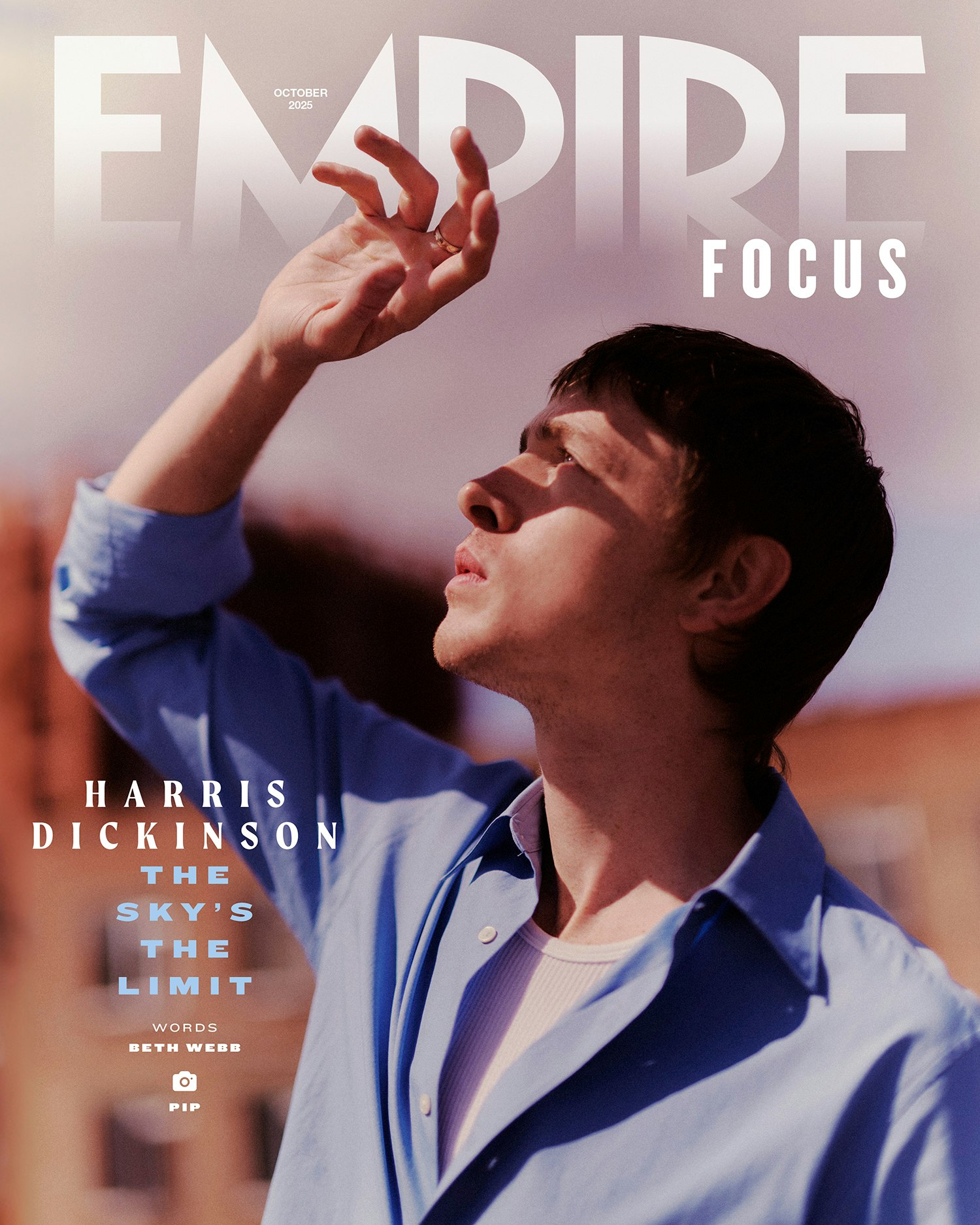

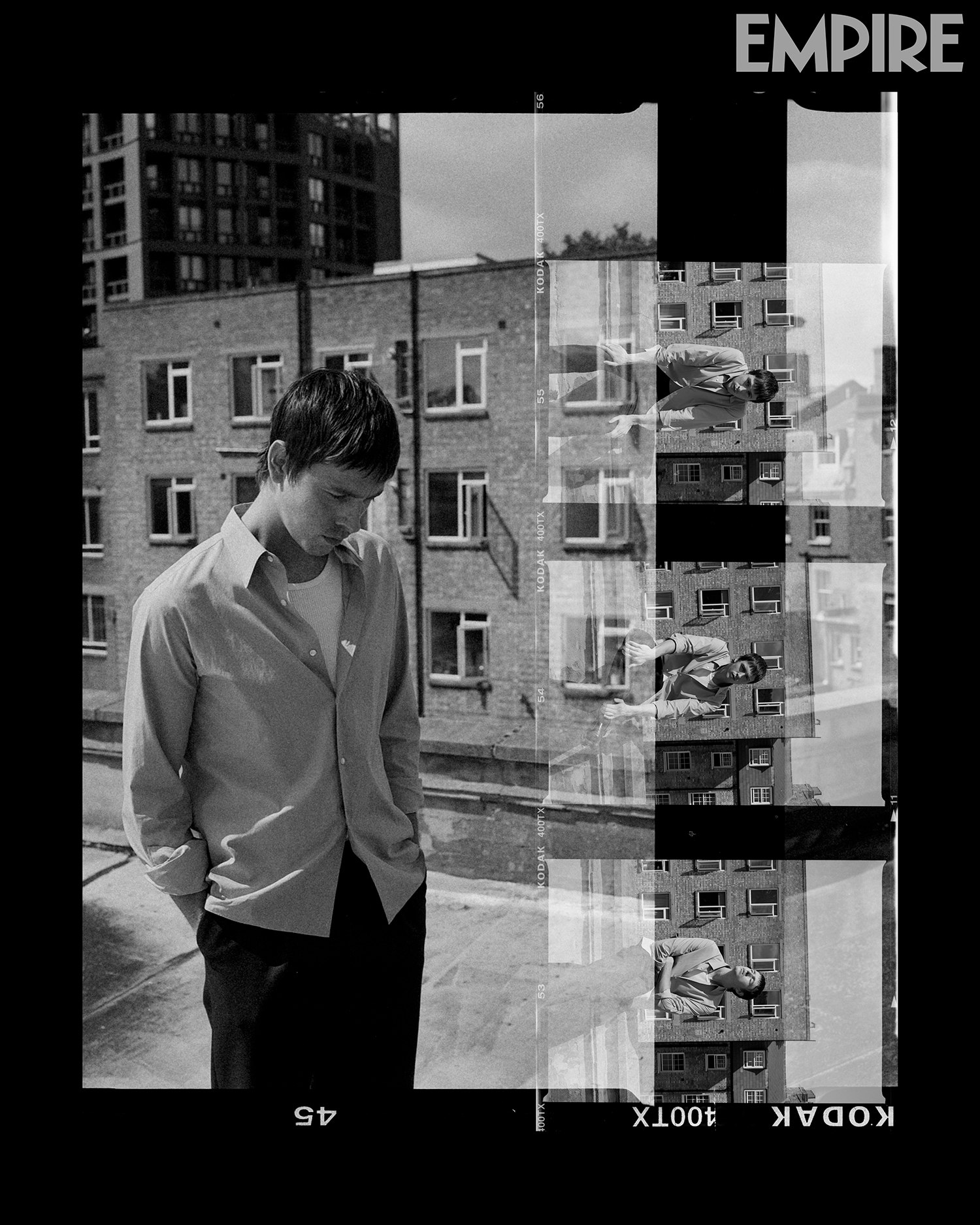

Dickinson recently set the internet ablaze via his muscular dance moves in Babygirl, while he is currently preparing for his most high-profile role to date, as John Lennon in Sam Mendes’ Beatles tetralogy, set for release in 2028. Yet when Empire catches up with the actor for our photo- shoot at a warehouse in his native East London, he brushes off, for reasons that will become clear, our suggestion that he’s on the brink of a new era.

Urchin is Dickinson’s feature debut as a writer-director. The story, which he started writing in 2020, follows Mike (Frank Dillane), a London outcast — and very much a knotty character — trying to land on his feet while navigating the rough waves of addiction and trauma. It’s a deeply personal film for Dickinson, not only because he works closely with his local homeless community, but because he pours his lived experience into every frame, from the jobs he worked as a kid to the lessons that he’s learned from Hollywood and beyond. Here in his hometown, he walks us through the journey that led him behind the camera, and where he’s headed next.

In Urchin, Mike feels like an extension of a lot of the characters that you’ve played. [Babygirl filmmaker] Halina Reijn described your performance in Beach Rats as “the boy and the man in one”. Why are you drawn to characters who veer between behaving like both?

Because that’s what we’re all doing, aren’t we? We’re all trying to pretend not to be these little kids that we once were. On a very Freudian level, we’re all trying to figure out how to navigate our lives in a way that’s deeply confusing. At least I feel that, and I’m constantly battling with my own understanding of adulthood and maturity and masculinity and how to move through the world in a way that feels “correct”.

How does that play out in Mike?

He’s rejected responsibility as a way of coping with his own trauma. You see that time and time again with people who have been through traumatic events; they reject any sort of accountability because it’s easier to do that. To escape. I was interested in the idea of a man-child who has never been able to find their own direction.

Physicality also feels important to you. In films like Triangle Of Sadness, Babygirl and The Iron Claw, you were putting your body out there in interesting, often challenging ways. Is that something that you’re seeking out more of?

Whenever I’m given a role that requires some sense of change, it’s always beneficial for me. I feel very in touch with my body. I like to move and dance. So I think that it’s natural for me to think about that side of it.

How does it feel to push your limits when it comes to your physicality?

The Iron Claw was specifically hard because it required muscle gain and a specific kind of training. I’ve pushed my body to both extremes. I lost a lot of weight when I was 21, 22, when I did a series with Danny Boyle [2018’s Getty oil-drama Trust]. There was a naivety to it. I didn’t really have a support network, I just did it on my own. I did it very unsafely, and I struggled with that and I have to rethink projects now because of that.

Was this something you were mindful of when you were working with Frank on Urchin?

Frank is a really physical performer. He really put himself through a lot and lost a lot of weight [to play Mike]. He messed up his shoulder because of how much he was hunching. I’d see that and I’d get worried because I’d also been on the other side of it. So as a director I was constantly making sure he’d had his food.

How else has your background in acting informed how you direct people?

It’s really vulnerable, isn’t it, acting? It’s an embarrassing process — well, it is for me — it’s a weird and humiliating thing, and feels rather silly at times. So I’m constantly having that in my head when I’m directing and creating the right setting for actors in order to feel comfortable. Then when comfortability comes, I think good performances can come because you’re able to access stuff and lose inhibition. If you’ve got the wrong settings, then it doesn’t work.

"I just loved behind-the-scenes videos. I was always rushing to the Blockbuster near us."

Beach Rats was your first time on a film set as a lead actor. How do you remember it?

It was a very small production with a very low budget. We were almost getting arrested for filming on the subway, and I thought that this was what all film shoots were like. I loved it — I wanted it to be guerilla because I’d been making short films as a kid like that. So I was like, “Great, this is a step up from that,” but the energy and the desperation is still there, and nothing else matters other than what we’re getting in the moment, and the sacred feeling of that. I was obsessed with it.

You watched a lot of films growing up, before you began acting. When did you start to notice things like camerawork and the craft of filmmaking?

I watched American Beauty when I was young and I remember seeing one of those top shots (signals a camera looking down) and thinking, “Oh, this is an extremely specific kind of camera.” The same with Donnie Darko — I have older brothers so they would often have films on that I probably shouldn’t have been watching. And then I just loved behind-the-scenes videos. I was always rushing to the Blockbuster near us; obviously they had VHS and DVDs and I’d be upset when they didn’t have the longer featurettes on them, because that was the perfect thing to watch afterwards.

Did you consult with directors you’d worked with while you were making Urchin?

It was more like beforehand. Ruben [Östlund] helped because we were filming the end of Triangle Of Sadness when I was editing my short film (2021’s 13-minute drama 2003, about a young soldier about to embark on a tour of duty). We were on the beach in Greece and the crew decided to do a small film festival because we had some time, and I had the film on my USB and I was like, “This is not ready but maybe I just… Fuck it, why not?” I spoke to Ruben about it and I was saying, “I want to change things but I can’t because it’s already locked,” and he was like, “It’s your film. Change it. Listen to your gut.”

Triangle Of Sadness introduced a lot of people to your comedic skills. Is humour important in your work?

Triangle Of Sadness certainly gave me a chance to perform in a different realm. Ruben is incredible at situational and observational comedy. I think that’s always been a big part of who I am, though. I love comedy and I’m quite stupid. Comedy was probably the route into acting for me (growing up, Dickinson made comedy shorts and Vines), because making people laugh has this weird empowerment thing. Good, smart comedy is hard to come by. It’s hard to crack.

Why did you choose to include humour in Urchin?

I think it was important, because the backdrop of the story could’ve very easily been bleak and misunderstood. From my experience and doing research within that community, I think that there’s a lot of humour in this world and with these people, because it’s a way out. People who have been to the extreme end of morality are often the ones who can be the most humorous. Because they’ve got nothing to lose.

You filmed part of Urchin in the London hotel where you used to work. How did it feel to be back?

It was wild and quite emotional. I stopped working there when I was about 21, and my impression was that it was still a hotel. But when we went back it had been bought by this private company and they were renting out the rooms as short-term accommodation. It had this sadness to it, because I had known it as a bustling hotel. It had faded and dampened and the ceiling had caved in. But I remember going back into the kitchen and the smell was the same. When I started writing the film I set it there, never with the expectation of shooting there, but because I knew the spaces so well.

What was your time working there like?

I worked a lot of late-night shifts and the manager was really kind to me. When I started to get auditions through he would let me take the time off. I remember I got an [acting] job and I quit the hotel. I was like, “That’s me done.” Then I finished the job and very quickly realised that it doesn’t work like that: you still need an income because that money’s gone already. So I limped back in and asked for my job back and he gave it to me.

"Admitting fear is always vulnerable."

You described Urchin being accepted into Cannes as “like taking your prized goat to the goat fair” and then worrying, “How did I end up here? My goat is not ready or good enough.” How do you feel about the goat now?

The goat did well. The goat did really well. I don’t know if the goat was ready but it jumped through the hoops, it did the tricks. People liked the goat. People stroked the goat, and perhaps the goat’s ego got a little big, and now the goat is ready to come back to reality.

The goat has come out during a time when your status is shifting, especially after the release of Babygirl, which seemed to broaden your fanbase. You’ve mentioned that you try to keep some distance from how you’re perceived by the public, but are you finding that harder to do now?

I’ve always tried to separate my own self from me as an actor in order for me to cope. Getting recognised has definitely picked up, which is a strange one. For the most part they’re positive encounters, which I feel lucky for. People just want to say something nice and that what you’ve done has resonated with them and then move on. It feels counter-intuitive to deny that; to pretend that you’re not in the public domain. But yeah, I think that separation is important, and not letting that define your sense of self. Not to be overly philosophical about it, but the more you engage with it, the more it will destabilise you. I’ve noticed that the more I engage with what’s being said, or with reviews, the less stable I feel. The best way is to understand it, have gratitude, and then carry on with the work.

Do you think that might be harder to do over the next few years?

I don’t know.

Is that scary?

(Pauses) Um, well, admitting fear is always vulnerable.

Because things are obviously going to be quite different during that time.

(Pauses) Why do you say that?

Because you’re playing John Lennon and the whole world and their dads will come to your doorstep.

(Laughing) Don’t say that!

"I’m in Beatles world, and I’m loving that, and it’s a great challenge."

Well, your metaphorical doorstep.

This thing is I just don’t believe that… (exhales). I just don’t think that I’m that interesting. I don’t think people care in that sense.

Even if you think that, the person you’re playing is very interesting to people.

Yeah, he’s a pretty interesting bloke. (Laughs) But I’m not him. I don’t know, it’s a speculative question, isn’t it? Check back in in four years. I’ll be a mess.

You had lunch with your Iron Claw co-star [Jeremy Allen White] last year while he was preparing to play Bruce Springsteen in Deliver Me From Nowhere. How did it feel to speak with someone who was embarking on a similar journey?

Well, he’d just started rehearsals, and I hadn’t started anything; I was in that comfortable, unfearful zone where I was floating along waiting for things to start. And he seemed just as comfortable, to be honest. I love Jeremy so much — he’s one of those actors I’m in awe of, even when I was working with him. And it made me feel like, yeah, I’ve got someone who understands a bit.

You’re simultaneously working on those huge films while promoting Urchin, which is very raw and personal. How are you finding pivoting between both worlds?

Again, for me there’s a real separation. Somehow I’m able to step between the two. It was easier because I had a year where I didn’t act and I just made Urchin. It was a clear focus. Now I’m promoting it and sharing it with the world. And I’m in Beatles world, and I’m loving that, and it’s a great challenge. I keep my mind on that, but step out. I think it’s unhealthy to have one sole thing that your brain is working on. It’s healthy for me to have a few things to work on, maybe to my sleep’s dismay.

You mentioned that American Beauty was a formative film for you. What’s it like now working with Sam Mendes, who directed it?

It’s wild, because that was his first film. The thing is, you deify these people and then you meet them and they’re also really lovely, humility-filled, silly people. That was refreshing when I started to meet Sam, because historically we’re led to believe that if someone’s a genius, they’re excused from being an arsehole. Particularly men. If men are rude, people will say, “Oh, but, they’re geniuses.” I don’t agree with that sentiment. You should be able to be a good person as well.

You’re very open about how competitive your industry is. Do you find that you compete with yourself?

I think that I’m the only person that I’m competitive with.

What are you competing for now?

I think the fear always exists in me that the goat is only as good as the last time it went to the fair. Maybe that’s all I’m thinking of — that I’ve got to continually try and do better than what I’ve done. It’s probably normal. I don’t think it’s a unique perspective. But I’m my own worst critic. My harshest critic. And I think that’s a coping thing. Like, if I’m super-hard on myself, then no-one else can break me.

It’s interesting to hear you say this in what feels like a milestone year for you.

But I think that if I didn’t do that then I would be complacent and then I’d probably just be crap. I’m a restless person, and it’s something that I’m trying to work on, but it drives me and it makes me want to find new things that challenge and scare me. It’s healthy in parts and unhealthy in others, but if I’m reaching for a certain thing, and I’m trying to do great stuff and work with great people, I can’t settle. It’s never a given. There was a time when I was a bit younger, when I was about three years in and I was auditioning and trying to get bits. And there was a point where I was like, “Maybe I don’t want to do this. Maybe I can’t handle not getting jobs.” To be in the place that I’m in now feels like such a stroke of luck.

You still feel that you’re here because of luck?

I’ve worked hard, and I’ve put in a huge amount of time and effort. But so do a lot of people. Not everyone gets the opportunity to work in the space that I do.

What does your filmmaking journey look like now that Urchin is done? Is there something you’re dying to do?

I want to direct seven Marvel films in a row.

Really?

No.

You have acted, though, in some big popcorn movies like Maleficent and The King’s Man. Would you ever want to direct one?

No, no, no. I want to make the films that I want to make. I want to make entertaining films — I’m definitely audience-conscious, especially after my first film. I want people to engage with my work on a wider level, like making great adult adventure stories. Sean Baker said at the London Film Festival that Anora is an adult cinema experience, and that’s what I want to do. I want to make films that are high-quality with incredible acting but have humour and that come directly from me in my own voice, that hasn’t been messed with. I don’t know exactly what that will be like. But I think that’s an okay ambition.

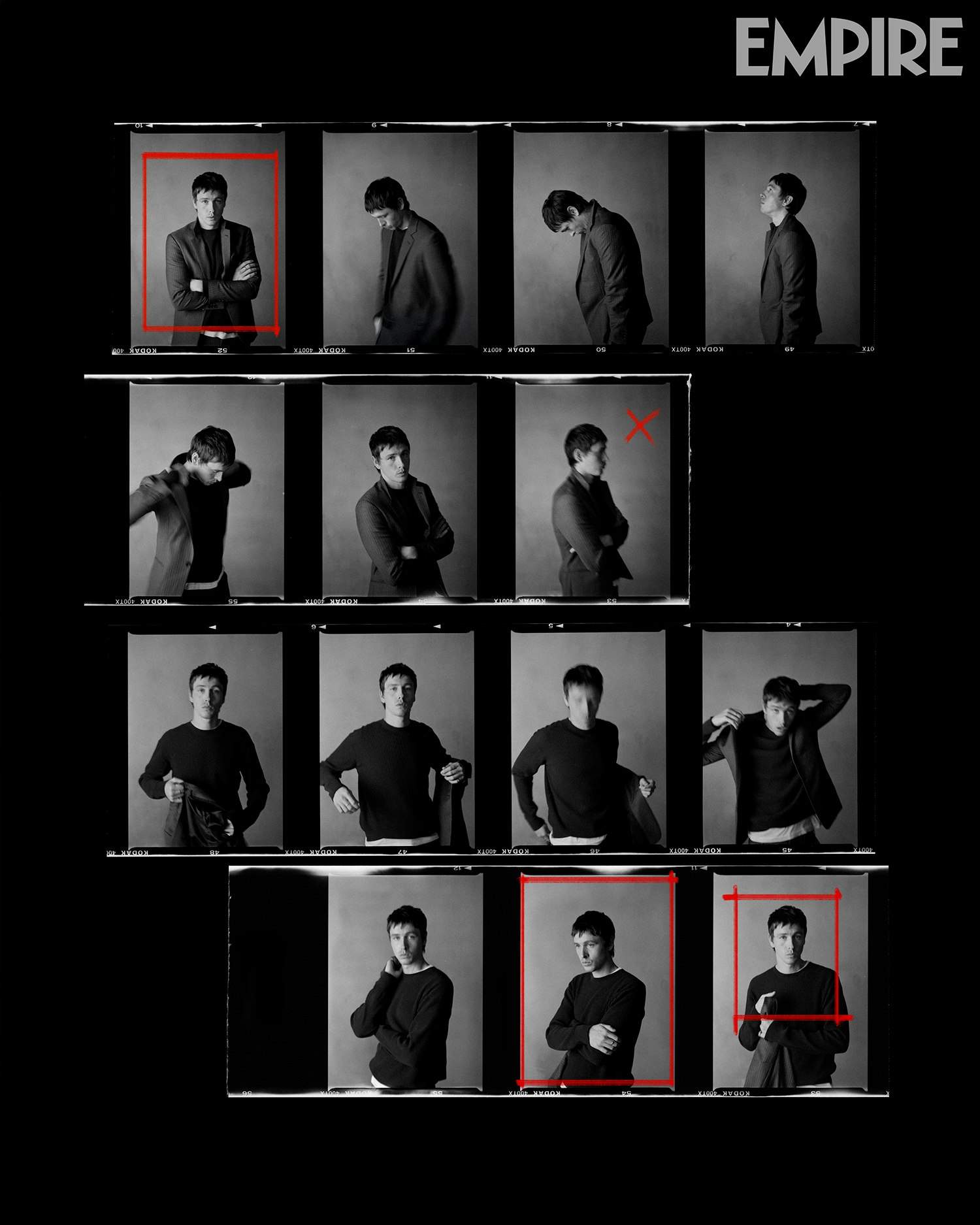

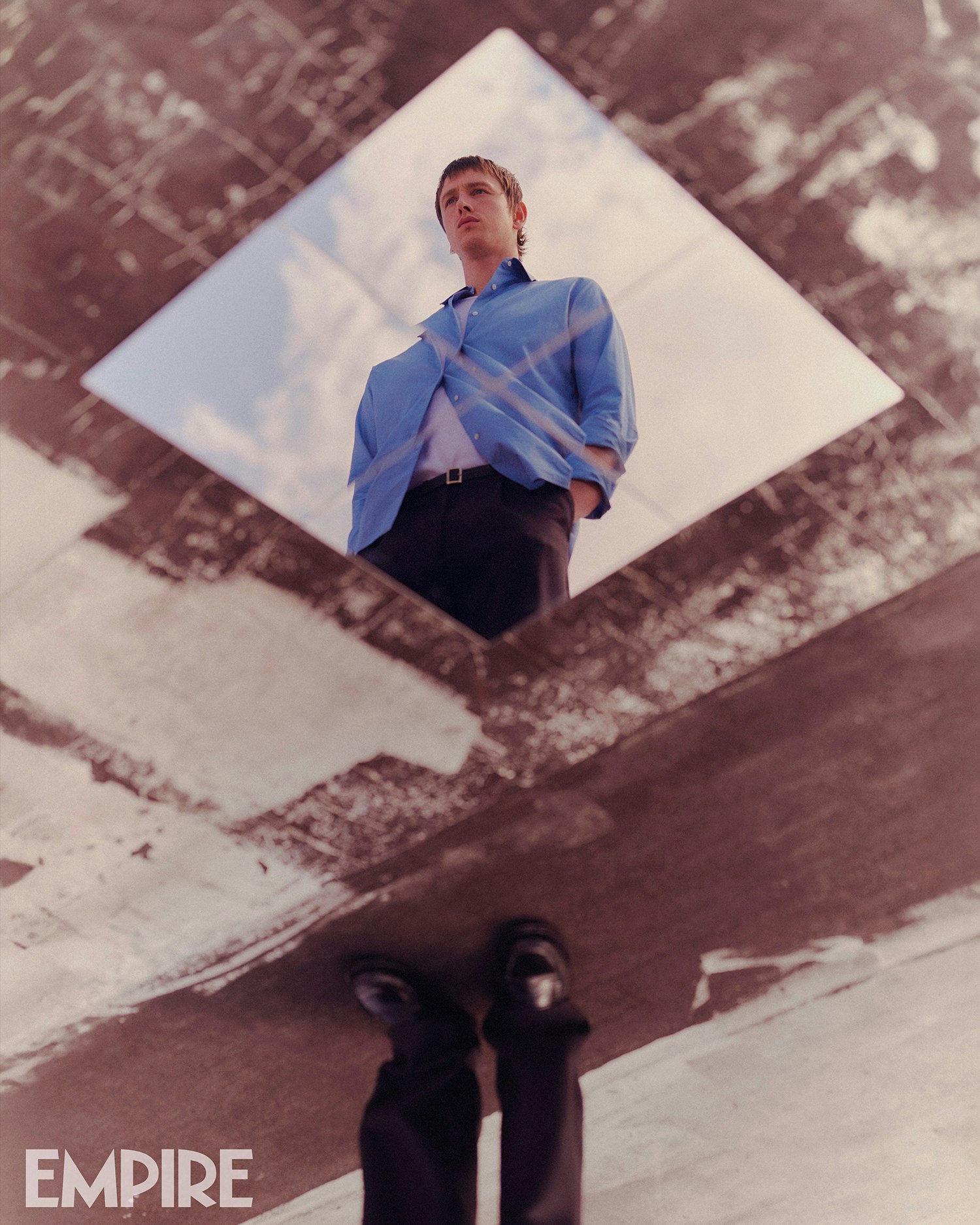

This article was originally published in the October 2025 issue of Empire. Harris Dickinson was shot exclusively for Empire in London on 5 August 2025 by Pip. Urchin comes to UK cinemas from 3 October.

What's Your Reaction?